Desktop Helper No. 7 - Pulmonary rehabilitation in the community - online

This is an online version of Desktop Helper No. 7 - Pulmonary rehabilitation in the community. Visit the linked page for a PDF and translations. References are available at the bottom of this page.

A Referrer’s Guide: The essential things you need to know about pulmonary rehabilitation to help breathless people breathe better, feel good and do more!

What is the essence of Pulmonary Rehabilitation?

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is a structured behavioural change programme tailored to an individual’s needs to reduce their breathlessness, improve their quality of life (including their fear of breathlessness), and improve their exercise capacity. The intervention therefore improves people’s ability to participate in daily life. It is a multi-model programme of exercise and self-management education to help people live better with chronic lung disease. It is fundamental to, and should be integrated into, their overall care. PR has also been shown to reduce the use of expensive services such as hospital inpatient care. It can be delivered safely in the community, outside of hospital. Despite its proven clinical and costeffectiveness, PR is widely underused. (1,2)

Who is PR for?

PR is for adults of all ages who are functionally limited by their breathlessness despite current management.

Why is it important?

People with chronic lung conditions like COPD become breathless with little exertion and this can be very frightening for them and their families or carers. As a result, people may avoid activities which make them breathless, leading to physical deconditioning, demotivation and potentially social isolation.

There are two essential messages to communicate, even if difficult for many breathless people to understand and healthcare professionals to convey:

“Breathlessness whilst moving around is NORMAL.”

“It is not harmful or dangerous to feel short of breath whilst moving.”

Your role in optimising acceptance and use of PR: consultation:

See the examples at www.ipcrg.org/PR

ASK about breathlessness “How has breathlessness changed your life?” “What troubles you most about being breathless?” Use a Breathlessness Scale e.g. MRC

ADVISE: “PR helps you breathe better, feel good, do more/return to work [if applicable] and I strongly recommend it. Have a look at what other breathless people say about it.”

ACT: Patients interested in going to PR will require support. What you say to them will depend on what support is available and accessible. But every patient can be congratulated and informed about the next step:

“That is an important decision, well done. I will now refer you...” either “... to the Pulmonary Rehabilitation programme” or “... to see an expert who can assess your breathlessness and decide on the right programme for you.” or

ACT: If they say no/not yet “It is your choice of course so let me know if you change your mind and I will ask again when we next meet. It is a great opportunity to meet others with a similar experience, to learn to control your breathlessness and to reduce the impact of your breathlessness on your life.”

Provide information and education about their condition and how they can best live with and manage their problems and medications e.g. Living Well and IPCRG. This will be reinforced in the programme.

Your role in optimising use of PR: planning

Highlighted examples at www.ipcrg.org/PR

As a referrer you can contribute to getting improved outcomes and programme efficiency because there can be obstacles: (3)

- Diagnosis - Person is not diagnosed or receives wrong diagnosis

- GP referral - GP does not believe in or communicate to the person the importance & benefits of PR

- Assessment - Person does not present for their assessment

- Start of Programme - Person does not turn up to begin their PR programme

- Ongoing Programme - Person does not complete the programme

- Maintenance - Person does not maintain activity after the programme

- Know the pathway and how to refer. Advocate for inclusive referral criteria and apply them.

- Limit “handoffs” between clinicians: e.g. refer to an expert to assess breathlessness or refer directly to a PR programme.

- Take a systematic approach to assessment of breathlessness: MRC breathlessness scale; algorithm

- Clarify the payment – know who will pay and how to get their commitment.

- Be aware of what PR is available, go and see a session.

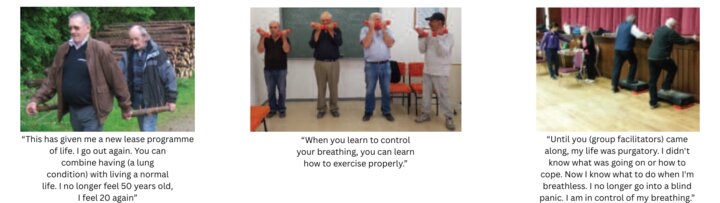

- Anticipate individual concerns about perceived lack of benefit/suitability: collect evidence of successes e.g. handwritten testimonies and photographs (with consent) or ask the provider for these or there may be a "graduate" of the programme who is willing to talk to the individual. Be confident and enthusiastic!

- Inform the wider community of its benefits and promote it using familiar and accessible language and stories.

- Get feedback from the providers about an individual’s progress and challenges (they will have 24 hours or more of direct contact).

- Think about offering psychological support, which may be a psychologist in the programme or peer support, or direct care or referral to a psychology service.

- Participate in audit to identify non-adherence. Modify your advice accordingly.

- Plan for drop-outs and allow re-entry into the programme.

What marks out a good programme?

If there is a choice or you have the authority to influence provision, select

a service that

- Has trained staff with expertise in chronic lung disease

- Tailors the programme to the individual’s specific physical, social, cognitive and psychological needs

- Offers on-the-spot personal advice on breathing techniques, and the psychological management of fear of breathlessness

- Prescribes and adjusts exercise using FITT principles (see below).

Setting up your own PR service: the basic elements

Setting up a Pulmonary Rehabilitation service from zero to help people breathe better, feel good and do more

View guidelines at www.ipcrg.org/PR and note conclusions from recent systematic reviews suggest there is no “right” way to provide it. Therefore we advocate adaptation to local circumstances: e.g. assessment, programme of prescribed exercises preferably face-to-face but possibly structured home-based with telephone or internet support, and flexible educational approaches. (4) We have used our network’s experience to offer guidance on how they do it.

The basic elements can be relatively easy to set up:

- Location: accessible. Assessment sites and group classes can be held in different locations. If transport is unavailable, consider homebased. Spread of locations may increase uptake.

- Facilities: a. For assessment: space for initial walk test. b. For programme: aim for a space for groups of 6 or more, available for a minimum of 1.5 hours twice a week (1 hour exercise, 30 mins education) for a minimum of 6 weeks. Replicate normal life as far as possible e.g. air-conditioning is not necessary; run programmes outdoors. Non-healthcare environments are acceptable. Consider including induction in a facility participants might use afterwards.

- Timing: should be flexible based on the needs of the participants to ensure maximum participation. Allow a rest day between exercise classes.

- Equipment: can be varied and low-tech as long as it delivers aerobic and strength training e.g. walking aids, dumbbells, bottles with sand, resistance bands, ankle weights; a phone or clickers for timing and to count; printed scoring systems for perceived difficulty of exercise, self-recording sheets and diaries for home sessions. Add pulse oximeters for assessment. For the education sessions: inhalers and inhaler technique training devices.

- Referral and feedback processes: negotiate this locally and aim for as many referral sources as possible. Write down the referral process and educate referrers about who, how and when to refer individuals (include current smokers and people using portable oxygen). Request referrer’s direct phone number/email to enable easy communication especially about attendance and post PR performance.

- Templates and tools: have simple templates and tools to support the assessment, prescription and progression of exercise and education for patients.

- Staff: use trained, knowledgeable staff e.g. physical therapist, nurse specialist, family physician. There is no right answer to the skillmix required to assess, deliver and support ongoing rehabilitation safely. It will depend on the local context and standards. Aim to create a team who can travel to different locations.

PR is an individually-tailored programme

A standard programme should be tailored to patient-specific physical, social, cognitive and psychological needs.

Assessment: also see www.ipcrg.org/PR

Holistic assessment is necessary to identify patients who will benefit and provide a baseline using validated assessment tools that can be used to evaluate the efficacy of the programme for individual and group outcomes. Therefore, assessment requires trained professional leadership to select and apply the right tools depending on the setting, systems and performance indicators. It should include:

- Exercise testing to measure exercise capacity and strength. The choice of test will allow for individualised exercise prescription e.g. incremental shuttle walk, sit to stand, grip strength

- Psychological: mood tends to improve during PR e.g. PHQ4 or HADS

- Quality of life e.g. for COPD: CCQ or CAT or CRQ

- Confidence/knowledge and understanding about COPD and/or level of activation

Importance of Exercise

The prescribed exercise programme must be personalised to gain benefit from the programme.

Exercise programmes should be designed according to the FITT principle and be as specific as a drug prescription:

Frequency (dose) e.g. minimum 6 weeks; aerobic exercise 5 days a week: 2 in a PR programme, 3 at home

Intensity (dose): use the initial test for endurance (minimum 60% VO2 max) supported by a perceived exertion scale and repetitions for strength (e.g. 10 rep max, or 50-80% of 1 Rep max or OMNI) e.g. 3 x 10 with a rest between sets

Time (duration): Aim for 30 minutes of continuous aerobic exercise (this doesn’t include warm up and cool down). If 30 mins is not possible aim to accumulate 30 mins and try to reduce rests.

Type (modality) e.g. aerobic: walking or cycling; strength: upper and lower limb exercises with weights (e.g. step-ups, sit to stand, biceps curls). Consider inclusion of flexibility, stretching and balance exercises as people with COPD are at risk of fracture due to osteoporosis and falls.

Delivering the programme

- Create a positive, fun, supportive environment.

- Exercise should be progressed weekly aiming for 5 sessions per week of 30 mins.

- Home exercise should be prescribed and monitored. The home programme should be based on the centre-based model of delivery.

Education:

Examples at www.ipcrg.org/PR

Teach breathing control techniques to be used during and after exercise. Offer psychological support to enhance coping (e.g. with fear of breathlessness, illness exacerbations, adjustment to lifestyle and identify changes) and to address barriers to adherence and completion, e.g. Cambridge model.

Also include:

- What is the condition and its cause(s);

- how to protect your lungs: smoking cessation and avoiding indoor biomass smoke, the role of physical activity;

- goal setting;

- relaxation;

- diet and nutrition;

- medicines optimisation;

- exacerbation plans;

- communication with the health team; advanced care and end of life;

- relapse prevention and maintaining changes.

Consider sharing these three issues of the IPCRG's COPD magazine to give more examples and information. They are available online incorporating videos, and some are also available in multiple languages and in PDF format.

Issue 1: Breathe Well, Move More, Live Better

Issue 2: Eat Well, Sleep Well, Feel Well

Issue 3: Plan, Take Action, Live Well with COPD

A Prescription for Success:

Examples www.ipcrg.org/PR

- Run 6-week programme with 2 sessions a week. Groups tend to be for 6-16 people. Test what works best balancing social cohesion and efficiency – a cohort: where participants stay together as a group; rolling: where participants can join at any point; semi-cohort/rolling: e.g. introducing new people every 4th week; roving: moves to different locations

- Deliver the prescribed programme that fits the space, e.g. 30 minute (min) aerobic: 5 min warm up, 30 min walking at prescribed pace, 5 min cool down. Aim for no rests. Strength exercise with weights for the legs and arms.

- Every week review and increase duration of exercise.

- Aim to build confidence to maintain activity after programme finishes e.g. induction at local facility. A plan for maintaining the benefits after the programme.

- If centre-based programme not possible, set up structured home-based programme supported with telephone monitoring.

References

- Glasziou 2017, Evidence for underuse of effective medical services around the world

- Griffiths 2001, Cost effectiveness of an outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation programme

- McCarthy 2015, Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Mathar 2015, Why do patients with COPD decline rehabilitation

Additional Information

This desktop helper aims to be practical: it is based on the IPCRG network’s own experience of trying to implement best practice with limited resources in low, middle and high income countries. It was generated from the evidence, guidelines and experience shared at an experience-led care meeting in May 2017

Note, an IPCRG position paper, making the case for Pulmonary Rehabilitation, is also available. Other resources available on www.ipcrg.org/PR

Authors: Siân Williams and Val Amies on behalf of the international expert group listed here.

Reviewer: Prof Sally Singh

Funding Statement: Boehringer Ingelheim funded the experience-led care meeting, writing & production. They took no part in the meeting or drafting.

This desktop helper is advisory; it is intended for general use and should not be regarded as applicable to a specific case.

Creative Commons Licence Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives.

The IPCRG is a Scottish-registered charity (No. 035056) and a Scottish company limited by guarantee (Company No. SC256268).

Communication address: 19 Armour Mews, Larbert, FK5 4FF, Scotland, United Kingdom.

Resource information

- Rehabilitation