Desktop Helper No. 6 - Evaluation of appropriateness of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) therapy in COPD and guidance on ICS withdrawal - online version

This is an online version of Desktop Helper No. 6 - Appropriate use and withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Visit the linked page for a PDF and translations. References are available at the bottom of this page.

The purpose of this desktop helper for the appropriate use and withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) is to:

- Help primary care clinicians identify patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who would benefit from ICS treatment compared to those in whom it may not be appropriate, and

- Provide guidance on how to withdraw ICS in patients with COPD in whom it is not needed.

The role of ICS in the treatment of patients with COPD

In COPD, evidence supports the use of an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) in combination with a long acting beta-agonist (LABA) or as part of a triple therapy regimen with the addition of a long acting muscarinic-antagonist (LAMA) to reduce the risk of symptomatic exacerbations.1 The effect of these regimens (ICS/LAMA/LABA and ICS/ LABA vs LABA/LAMA) is greater in patients with high exacerbation risk (≥2 exacerbations and/or 1 hospitalization in the previous year).2–4 However, until recently there has been no consistent evidence on the long-term effects of ICS on mortality or the group of patients who would benefit most. (1)

Recent studies have shown that blood eosinophil counts predict the effect of ICS in preventing future exacerbations in COPD3,5 and they can be used as a biomarker to estimate the benefits of adding ICS to regular bronchodilator treatment for individual patients. (1)

Adverse effects associated with ICS therapy

There is high quality evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that ICS use is associated with many adverse effects including oral candidiasis, hoarse voice, skin bruising and pneumonia and results of observational studies suggest that ICS treatment could also be associated with increased risk of diabetes/poor control of diabetes, cataracts, osteoporosis, fracture and mycobacterial infection including tuberculosis. (1)

Current recommendations on ICS use for patients with COPD

IPCRG Guidance on when to begin ICS in patients with COPD

- Consider ICS combined with broncho-dilators as initial treatment in a recently diagnosed patient and/or a patient who is pharmacological treatment “naïve” based on the history of asthma, risk of exacerbation, and eosinophils as shown in Table 1.

- Consider ICS after reassessment of patients with COPD not previously treated with ICS based on risk of exacerbations and eosinophils as shown in Table 1.

In both cases, optimal bronchodilation is critical.

Table 1 - IPCRG Guideance on when to begin ICS in patietns with COPD. First optimise bronchodilation

1. Inital treatment:

a. Well documented previous history of asthma, especially if diagnosis under 40 years’ old

b. ≥2 moderate exacerbations or 1 hospitalization in the previous year and >300 eosinophils μL−1

2. Reassessment†

a. ≥2 moderate exacerbations or 1 hospitalization in the previous year* and >300 eosinophils μL−1*

b. ≥2 moderate exacerbations or 1 hospitalization in the previous year* and eosinophils μL−1 >100 but <300 after carefully balanced risk-benefit considering:

o Recent pneumonia

o Confirmed bacterial colonization

o Bronchiectasis

o Comorbidities, especially diabetes and osteoporosis or those at risk for these conditions

† Patient not previously on ICS

* Or since previous assessment if less than 12 months

____________________

Current use of ICS for patients with COPD

Despite recent recommendations that ICS use should be reserved for a small proportion of patients with COPD, there is evidence of continued inappropriate use of ICS in these patients. Guidelines implementation has been inconsistent as evidenced by numerous studies showing inappropriate prescription or over-prescription of ICS by up to 50%, a situation that has also been shown in the IPCRG UNLOCK study. (8)

Evidence for ICS withdrawal in patients with COPD

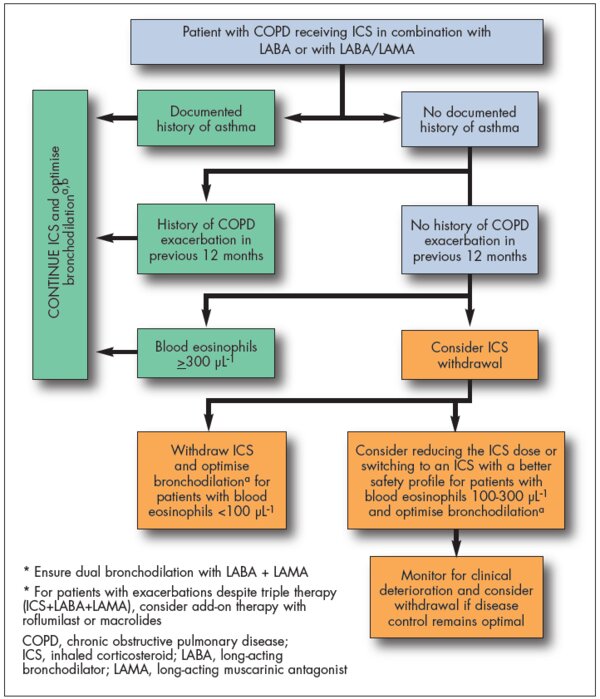

IPCRG Guidance on when and how to withdraw ICS in patients with COPD

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). 2020 Global Strategy for Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD. Available at: https://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/

- Wedzicha JA, et al. Indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. NEJM 2016;374:2222–34.

- Lipson DA, et al. Once-daily single-inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. NEJM 2018;378:1671–80.

- Papi A, et al. Extrafine inhaled triple therapy versus dual bronchodilator therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRIBUTE): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018;391:1076–84.

- Bafadhel M, et al. Predictors of exacerbation risk and response to budesonide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a post-hoc analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet Respir Med 2018;6:117–26.

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Asthma, COPD and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS), 2015. Available at: https://goldcopd.org/asthma-copd-asthma-copd-overlap-syndrome/

- Agusti A, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: friend or foe? Eur Respir J 2018;52(6)

- Tsiligianni I, et al. COPD patients' characteristics, usual care, and adherence to guidelines: the Greek UNLOCK study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2019;14:547–56

- Rossi A, et al. INSTEAD: a randomised switch trial of indacaterol versus salmeterol/fluticasone in moderate COPD. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1548–56

- Rossi A, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids can be safe in COPD patients at low risk of exacerbation: a real-life study on the appropriateness of treatment in moderate COPD patients (OPTIMO). Respir Res 2014;15:77

- Magnussen H, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. NEJM 2014;371:1285–94

- Suissa S, et al. Discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk reduction of pneumonia. Chest 2015;148:1177–83

- Watz H, et al. Blood eosinophil count and exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids: a post-hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4:390–8

- Chapman KR, et al. Long-term triple therapy de-escalation to indacaterol/ glycopyrronium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (SUNSET): A randomized, double-blind, triple-dummy clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198:329–39

- Vogelmeier CF, et al. Efficacy and safety of direct switch to indacaterol/ glycopyrronium in patients with moderate COPD: the CRYSTAL open-label randomised trial. Respir Res 2017;18:140

- Frith PA, et al. Efficacy and safety of the direct switch to indacaterol/ glycopyrronium from salmeterol/fluticasone in non-frequently exacerbating COPD patients: the FLASH randomized controlled trial. Respirology 2018; 23:1152–9

- Buhl R, et al. Dual bronchodilation vs triple therapy in the "real-life" COPD DACCORD study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018;13:2557–68

Additional Information

Authors: Miguel Román-Rodríguez (Family Physician and Department of Chronic Respiratory Diseases in Primary Care, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Baleares (IdISBa), Palma de Mallorca); Ioanna Tsiligianni (Family Physician and Assistant Professor, Clinical of Social and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Crete, Greece); Siân Williams (International Primary Care Respiratory Group, London)

Reviewers: Alan Kaplan (Chair Family Physician Airways Group of Canada, Vice President Respiratory Effectiveness Group); David Price (Director of Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute [OPRI], Director of Optimum Patient Care Global, UK and Australia and Professor of Primary Care Respiratory Medicine, University of Aberdeen, UK)

Editor: Tracey Lonergan (High Peak Communications Ltd, UK)

This desktop helper was self-funded by IPCRG.

This desktop helper is advisory; it is intended for general use and should not be regarded as applicable to a specific case.

Creative Commons Licence Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives.

The IPCRG is a Scottish-registered charity (No. 035056) and a Scottish company limited by guarantee (Company No. SC256268).

Communication address: 19 Armour Mews, Larbert, FK5 4FF, Scotland, United Kingdom.

Resource information

- COPD

- Treatment - drug

- COPD Right Care

- COPD

- Management

- Clinical Education