Desktop Helper No. 12 - COPD and Mental Health: Holistic and Practical Guidance for Primary Care - online

This is an online version of Desktop Helper No. 12 - COPD and Mental Health: Holistic and Practical Guidance for Primary Care. Visit the linked page for a PDF, translations, more information and related resources. References are available at the bottom of this page.

This desktop helper aims to raise awareness of the challenge of identifying and managing mental health problems in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and to direct primary care professionals (PCPs) to assessment tools as well as non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions.

Introduction

Mental health problems, including anxiety and depression, are common among people with COPD and substantially impact their quality of life (QoL). In countries where tobacco smoking is prevalent, tobacco dependence is an additional factor that can significantly impact on QoL of people with COPD. However, PCPs often have low confidence to treat these problems due to the complex inter-relationships between them and symptoms such as breathlessness, which make assessment and treatment challenging. Estimates suggest that about 30% of people with COPD have comorbid depression (increasing to up to 80% with increasing COPD severity), and between 10% and 50% have comorbid anxiety. (1–3) Prevalence increases with age and as symptoms of COPD worsen, and they can co-exist. (3–6) Globally, about 20% of people smoke tobacco, (7) although this varies by country, and about 20% of them will develop COPD.8 Despite this increased risk, smoking rates remain high following a diagnosis of COPD. (9,10) Mono-disease guidelines that focus on only one element are inadequate and guidance for PCPs is lacking.

COPD and mental health

Despite strong evidence of a high prevalence of depression and anxiety in people with COPD these comorbidities are underdiagnosed and undertreated. COPD-related depression and/or anxiety is associated with poorer QoL, more persistent smoking, worse adherence to treatment plans, more hospital admissions, readmissions and exacerbations, lower self-management rates, poorer survival and higher care costs than for people without psychological comorbidities. (11) Indeed, breathlessness, depression, anxiety and exercise tolerance are more correlated with health status than the widely used spirometric values. (12) People with COPD often report feelings of isolation and mental illness can increase this isolation due to societal and self-imposed stigma resulting in a cycle of decline which can impact QoL and impair adherence to COPD treatment. (13,14)

Breathlessness and psychological distress

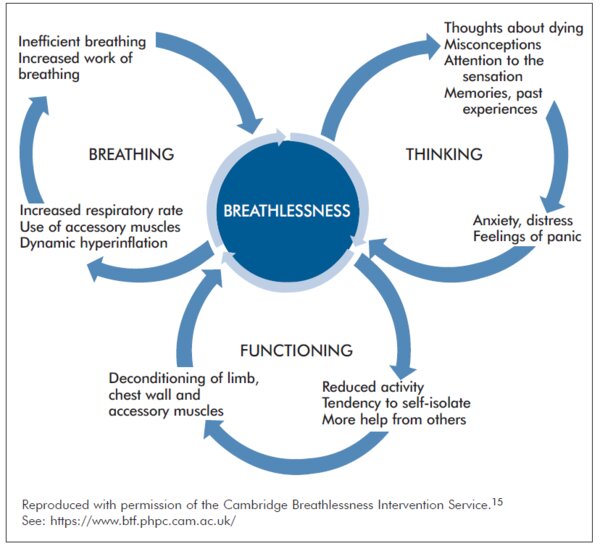

Breathlessness is a core and complex symptom among people with COPD. It is not only the subjective perception of breathlessness but a person’s reactions and responses to the sensation that matter. (15)

The ‘Thinking’ negative cycle in the Breathing-Thinking-Functioning (BTF) model (see diagram above) offers a way of understanding how thoughts affect and are affected by breathing and also physical activity; it also suggests how we can break these cycles. (15) Attention to the sensation of breathlessness, memories of past experiences, misconceptions and thoughts about dying can contribute to anxiety, feelings of panic, frustration, anger and low mood, which in turn reinforce unhelpful and unrealistic thoughts and images. Conversely, interventions to address these negative thoughts in relation to breathlessness and manage symptoms of anxiety and low mood have the potential to improve QoL and improve adherence to COPD treatment.

Tobacco use and poor mental health

While smoking rates are not high among people with COPD in all countries, where they are, the strong association between tobacco use and poor mental health should be considered. Tobacco smokers with mental health disorders tend to be more addicted to smoking, smoke more cigarettes and are more likely to relapse and therefore need support for repeated attempts at quitting. (16–19)

Smoking, depression, and anxiety are all associated with higher risk of death in people with COPD. The risk of death, depression and anxiety increases with increasing duration of smoking (years) and cigarette pack-years. (20) Yet smoking cessation is effective and is the most important intervention to slow the progression of COPD, increase survival and reduce morbidity. (5,21,22)

Contrary to popular belief, quitting reduces anxiety and depression. Indeed, the effect size is as large or larger than antidepressants for mood and anxiety disorders. (23,24) It can be challenging to differentiate between symptoms of anxiety and of withdrawal, so assess anxiety levels at each appointment.

Action points to identify mental health problems in people with COPD

Treatment of mental health problems in people with COPD

Table 2 :OARS

O - Open questions - To learn about their feelings and beliefs e.g. “Would you like to tell me more about how you feel?” “How do you experience breathlessness?”

A - Affirmations - Be positive and reinforcing; build a relationship and demonstrate empathy “It’s great that you are willing to discuss your sadness, I am here to help you.”

R - Reflection - “It sounds as though you have thought a lot about your symptoms and you know what to do.”

S - Summary - “So let’s make a summary of what we discussed.”

Source: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/394208/Session-5.pdf

________________________________________________________________________

Non-pharmacological interventions

Cochrane reviews concluded a structured cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approach may be effective in reducing depression and anxiety symptoms. (1,26) This approach is feasible and cost-effective in the community delivered by trained practitioners. (27) Incorporating a CBT approach to address breathlessness in COPD and supporting self-management has the potential to increase willingness to engage with treatment including behavioural activation and physical activity, which can also be helpful for anxiety and depression.(28–31)

Table 3 details a range of interventions that may be useful to address breathlessness. We appreciate not all of these are accessible, translated, validated, affordable or culturally acceptable in every country, but the list is varied so include those which might be accessible in your setting. For example, the Cambridge Breathlessness Intervention Service offers a range of interventions to address breathlessness related to the "thinking" vicious cycle. (15)

Holistic care of the person with COPD and comorbidities such as anxiety and depression may be delivered via a multidisciplinary team, where available, who can deliver some or all of the interventions outlined above as well as pulmonary rehabilitation (PR). PR improves anxiety and depression symptoms. (32) However, practitioners under-refer, and people with COPD commonly fail to attend, or complete, their PR course; we await results of the TANDEM trial which is incorporating CBT to improve PR uptake. (2) Exercise in the natural environment has many therapeutic benefits, for both mental and physical health. (33) Taking part in nature-based activities helps people who are suffering from mental ill-health and can contribute to a reduction in levels of anxiety, stress and depression. (34) There are no specific studies in people with COPD.

Table 3: Interventions to address breathlessness

| Intervention | Purpose/aim | Supporting evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive behavioural therapy | Problem-solving approach that challenges unhelpful behavioural thoughts/behaviours; reduces anxiety in COPD in short term; therapy increases pulmonary rehabilitation attendance. | Yohannes AM, et al. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18: 1096.e1-1096.e17. Heslop-Marshall K, et al. ERJ Open Res 2018;4: 0094-2018. Pumar MI, et al. J Thorac Dis 2019;11(Suppl 17): S2238–S2253. |

| Mindfulness/ meditation |

20-minute mindful breathing reduces breathlessness in lung disease, and anxiety/depression in advanced disease; enhances non-evaluative attention and may increase self-efficacy. |

Seetee S, et al. J Med Assoc Thai 2016;99:828–8. Malpass A, et al. BMJ Open Respir Res 2018;5:e000309. Tan SB, et al. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57:802–8. Look ML, et al. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2021; 11:433–9. |

| Relaxation techniques |

Some evidence that relaxation interventions can help anxiety, breathlessness and fatigue in COPD. Guided imagery (‘thinking of a nice place’), progressive muscular relaxation and counting are most acceptable. |

Hyland ME, et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016; 11:2315–9. Yilmaz CK, Kapucu S. Holist Nurs Pract 2017;31:369–77. Volpato E, et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015;2015:628365. |

| Acupuncture/ pressure | Improves breathlessness in advanced disease and may reduce anxiety. | von Trott P, et al. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;59: 327–338.e3. |

| Singing therapy | Most evidence suggest singing therapy can improve lung function; some evidence suggest it may improve anxiety and QoL; anecdotal evidence of value. |

Gimenes Bonilha A, et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2009;4:1–8. Lord VM, et al. BMC Pulm Med 2010;10:41. McNamara RJ, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 12:CD012296. |

| Positive psychology giving sense of control/ confidence | Not evidence-based. However, holistic breathlessness services reduce anxiety/depression and use positive psychology, improving self-efficacy. |

Brighton LJ, et al. Thorax 2019;74:270–81. Lovell N, et al. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57: 140–155.e2. |

| Social presence | Experimental evidence in healthy volunteers for social presence reducing breathless perception; patients describe reassurance from presence of others. | Herzog M, et al. Biol Psychol 2019;140:48–54. |

Pharmacological interventions

Effective management of breathlessness using bronchodilator therapy (5) will contribute to easing psychological distress. Treat tobacco dependence with available pharmacotherapy as well as counselling. Recommendations regarding antidepressant medications for people with COPD are lacking. (11) However, we suggest reasonable approaches to management include the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; preferred) or, if not available or not appropriate for other clinical reasons, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) may be a second-line option for the treatment of depression. (11) Avoid using TCAs in people with severe COPD, due to an increased risk of respiratory centre depression and respiratory failure. Anxiety may be managed using SSRIs but the evidence is weak. (35) Despite widespread use of benzodiazepines for COPD, evidence suggests it does not help with breathlessness and should not be used for this indication. (36) They may be considered for people with acute distressing anxiety for short-term use (no more than 4 weeks) and at the lowest dose possible. (37) Metabolism of antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs is increased in tobacco smokers who are therefore likely to need higher doses than non-smokers. Success in quitting means you may need to reduce the dose to compensate for this. (38)

When to refer

Refer (or direct) people with COPD to appropriate mental health services where available, including psychology if the patient expresses a preference for non-pharmacological care, or the management of anxiety or depression is not achieved with the interventions available to you. People with COPD and psychosis or suicidal ideation require immediate referral to specialised mental health services.

Conclusions

References

- Pollok J, van Agteren, Esterman AJ, et al. Psychological therapies for the treatment of depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;3:CD012347

- Sohanpal R, Pinnock H, Steed L, et al. Tailored, psychological intervention for anxiety or depression in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), TANDEM (Tailored intervention for Anxiety and Depression Management in COPD): protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2020;21:18(2020).

- Yohannes AM, Alexopoulos GS. Depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Eur Respir Rev 2014;23:345–9.

- Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012 ;380 :3743.

- GOLD 2022 Report. Available at: https://goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports-2/. Accessed March 2022.

- Wagena EJ, Arrindell WA, Wouters EFM, et al. Are patients with COPD psychologically distressed? Eur Respir J 2005;26:242–8.

- Ritchie H, Roser M. Smoking. 2021. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/smoking. Accessed March 2022.

- Terzikhan N, Verhamme KMC, Hofman A, et al. Prevalence and incidence of COPD in smokers and non-smokers: the Rotterdam Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:785–92.

- Stegberg M, Hasselgren M, Montgomery S, et al. Changes in smoking prevalence and cessation support, and factors associated with successful smoking cessation in Swedish patients with asthma and COPD. Eur Clin Respir J 2018;5:1421389.

- Vogelmeier C, Hederer B, Glaab T, et al. Tiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPD. New England J Med 2011;364:1093–103.

- Pollok J, van Agteren JE, Carson-Chahhoud KV. Pharmacological interventions for the treatment of depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018 ;12 :CD012346.

- Tsiligianni I, Kocks J, Tzanakis N, et al. Factors that influence disease-specific quality of life or health status in patients with COPD: a review and meta-analysis of Pearson correlations. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:257–68.

- Stuart H. Fighting the stigma caused by mental disorders: past perspectives, present activities, and future directions. World Psych 2008;7:185–8.

- Kassis IT, et al. Treatment non-compliance of psychiatric patients and associated factors: are patients satisfied from their psychiatrist? Br J Med Med Res 2014;4:785–96.

- Spathis A, Booth S, Moffat C, Hurst R, Ryan R, Chin C, et al. The Breathing, Thinking, Functioning clinical model: a proposal to facilitate evidence-based breathlessness management in chronic respiratory disease. npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine. 2017;27(1):27.

- Berlin I, Covey LS. Pre-cessation depressive mood predicts failure to quit smoking: the role of coping and personality traits. Addiction 2006;101:1814–21.

- Coulthard M, Farrell M, Singleton N, Meltzer H. Tobacco, alcohol and drug use and mental health. Office for National Statistics (ONS) 2002.

- Royal College of Physician, Royal College of Psychiatrists. Smoking and mental health. 2013.

- Ho SY, ALnashri N, Rohde D, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of depression on subsequent smoking cessation in patients with chronic respiratory conditions. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2015;37:399–407.

- Lou P, Chen P, Zhang P, et al. Effects of smoking, depression, and anxiety on mortality in COPD patients: a prospective study. Respir Care 2014 ;59 :54–61.

- Williams S, et al. IPCRG Position paper No. 1 – Primary care and chronic lung disease. Available at: https://www.ipcrg.org/primaryrespiratorycare. Accessed March 2022.

- Tonnesen P. Smoking cessation and COPD. Eur Respir Rev 2013 ;22 :37–43.

- Rigotti NA. Smoking cessation in patients with respiratory disease: existing treatments and future directions. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1:241–50.

- Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, et al. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014 ;348 :g1151.

- Harrison SL, Robertson N, Goldstein RS. Exploring self-conscious emotions in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A mixed methods study. Chron Respir Dis 2017;14:22–32.

- Usmani ZA, Carson KV, Heslop K, et al. Psychological therapies for the treatment of anxiety disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017 ;3 :CD010673.

- NICE guideline CG124. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg123. Accessed March 2022.

- Aylett E, Small N, Bower P. Exercise in the treatment of clinical anxiety in general practice – a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:559.

- Hu MX, Turner D, Generaal E, et al. Exercise interventions for the prevention of depression: a systematic review of meta-analyses. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1255.

- Newham JJ, Presseau J, Heslop-Marshall K, et al. Features of self-management interventions for peoples with COPD associated with improved health-related quality of life and reduced emergency department visits: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulm Dis 2017 ;12 :1705–20.

- NICE guideline. NG115. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115/chapter/Recommendations. Accessed March 2022.

- Gordon CS, Waller JW, Cook RM, et al. Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on symptoms on anxiety and depression in COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2019;156:80–91.

- Natural England. Links between natural environments and mental health: evidence briefing (EIN018). 2016. Available at: http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/5748047200387072. Accessed March 2022.

- Krzanowski J, et al. Green Walking in mental health recover: A Guide. 2020. Available at: https://sustainablehealthcare.org.uk/green-walking. Accessed March 2022.

- Usmani ZA, Carson KV, Cheng JN, et al. Pharmacological interventions for the treatment of anxiety disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;11:CD008483.

- Simon S, Higginson I, Booth S, et al. Benzodiazepines for the relief of breathlessness in advanced malignant and non-malignant diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2010:1:CD007354.

- NICE. BNF. Hypnotics and anxiolytics. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/hypnotics-and-anxiolytics.html. Accessed March 2022.

- NCSCT. Smoking cessation and smokefree policies: Good practice for mental health services. Available at: https://www.ncsct.co.uk/usr/pdf/Smoking%20cessation%20and%20smokefree%20.... Accessed March 2022.

- IPCRG. Desktop Helper No. 4 - Helping patients quit tobacco - 3rd edition. Available at: https://www.ipcrg.org/desktophelpers/desktop-helper-no-4-helping-patient.... Accessed March 2022.

Additional Information

Authors: Ioanna Tsiligianni, Siân Williams

Contributor: Anna Spathis

Reviewers: Steve Holmes, Nazim Uzzaman, Oscar Flores-Flores

Editor: Tracey Lonergan

This desktop helper was funded from an educational grant from Boehringer Ingelheim who provided a grant to support the development, typesetting, printing and associated costs but did not contribute to the content of this document.

This desktop helper is advisory; it is intended for general use and should not be regarded as applicable to a specific case.

Creative Commons Licence Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives.

The IPCRG is a Scottish-registered charity (No. 035056) and a Scottish company limited by guarantee (Company No. SC256268).

Communication address: 19 Armour Mews, Larbert, FK5 4FF, Scotland, United Kingdom.

Resource information

- COPD

- Disease management

- Rehabilitation

- Treatment - drug

- Treatment - non-drug

- COPD Right Care

- COPD

- Management

- Risk Factors